Wooden Churches on the Move: Negotiated Modernity between Village and Nation in the Carpathian Mountains, 1918 - 1939

Doctoral project: Radu-Remus Macovei

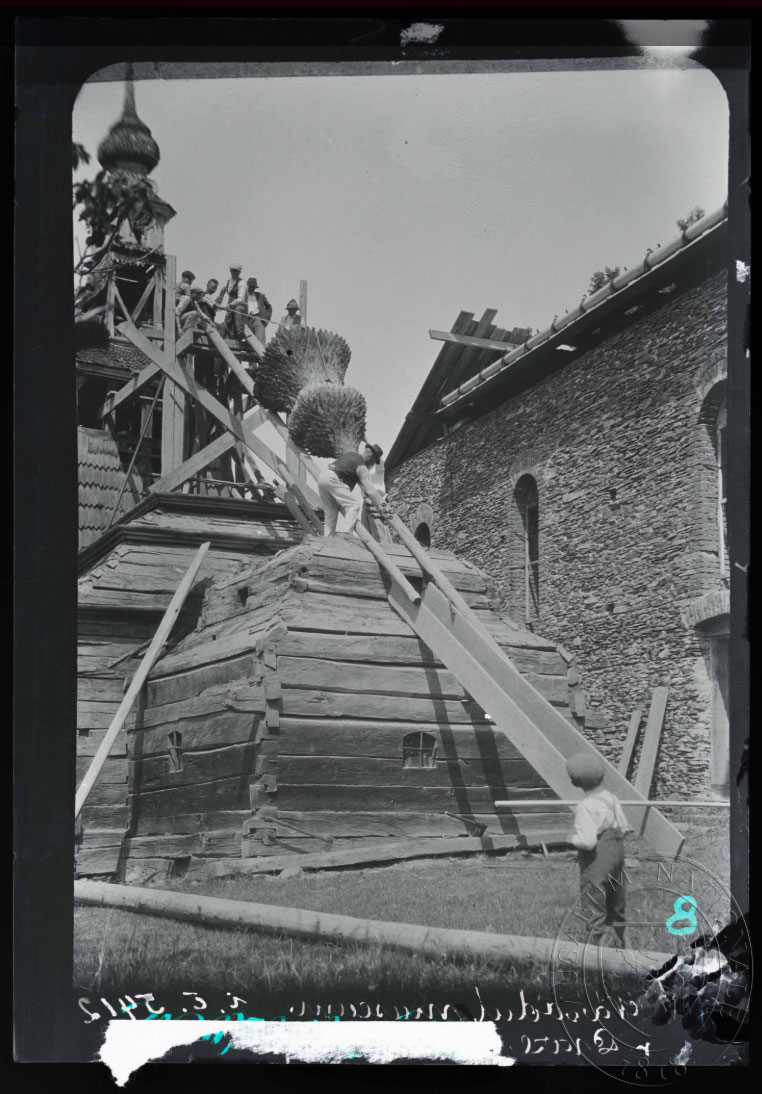

Many wooden churches in the Carpathian Mountains region of Eastern Europe were physically relocated in the interwar period after the fall of Austria-Hungary. Through the process of wooden church mobility, architecture became the locus of a negotiated modernity that intersected the competing visions of local communities and national institutions. Starting from three transnational case-studies in interwar Romania, Czechoslovakia and Polish-ruled Ukraine where wooden churches were exchanged for other resources in grassroots and state-led processes of building duplication, rural extraction, urban insertion and building multiplication, the project hypothesizes that Carpathian communities and national institutions negotiated a modernity that challenges dominant imperial, national and ethnocentric historiographies.

The literature has situated the Carpathian wooden churches in (1) world history surveys connecting them to wider cultural influences, (2) national history surveys linking the wooden churches to national and ethnicidentity and (3) case-studies related to specific social or material findings. In imperial and national historiographies, it is argued that Carpathian wooden churches demonstrate multi-ethnic unity and hierarchy or ethnic exceptionalism.1 The Carpathian wooden churches’ relocation processes are prime sites for exposing the entanglements between tradition and modernity and are ripe for revisiting outside of ethnocentric approaches, focusing instead on regional and transnational exchange in a material and institutional history of the region. Across the literature, the wooden churches are treated as special subjects of study in the field of vernacular architecture where tradition and modernity are seen in a binary relationship.2 However, recent scholarship has posited that the two mutually inform each other, proposing multiple modernities that unsettle dominant institutionalized histories.3 Indeed, in Eastern Europe’s interwar period, national discourses oscillated between valorizing supposedly vanishing ‘folk’ cultural products and modernizing the ‘backward’ countryside, while Carpathian communities were constructing their own modernities in brick and mortar to replace nailless wooden constructions. National institutions responded by legislating preservation, setting up museums and physically relocating community-owned wooden churches from the countryside to cities. This latter practice locates architecture at the core of frictions between local communities and national entities.

To reconstruct the modernity negotiated by national institutions and Carpathian communities, this study breaks down relocation processes into four key moments: building duplication, rural extraction, urbaninsertion and building multiplication. The project deploys archival research, oral history interviews, and published primary and secondary sources and analyzes the collected material through provenance, ekphrasis, regional and transnational approaches and postcolonial studies. These collection and analytical methods allow inductive reasoning, examining larger theoretical concepts of modernity, tradition, exchange, nation-building and coloniality through microhistories.

1 Oxana Gourinovitch, “The Revenge of the Future,” in Popescu et al., “Field Notes,” 10.

2 Abu-Lughod, “Disappearing Dichotomies: First World - Third World; Traditional - Modern,” 8.

3 Brown and Maudlin, “Concepts of Vernacular Architecture,” 349.

I. f. Geschichte/Theorie der Arch.

Stefano-Franscini-Platz 5

8093

Zürich

Switzerland